APTIS Reading part 4 ejercicios

/Reading Aptis matching headings

¡Muy buenas!

Lo primero es lo primero, esperamos que estéis todos bien y a tope con el inglés. Si ya habéis hecho los ejercicios de Reading Aptis General part 1, part 2 y part 3, ahora os traemos ni más ni menos que la parte más retadora del examen Aptis: reading Aptis matching headings.

En ésta parte del Reading Aptis General tenéis que asignar un título a un párrafo (matching headings to paragraphs reading) y, bueno, no es precisamente a piece of cake. Os dejamos como viene siendo costumbre 5 ejercicios readings Aptis General part 4 que la practiquéis.

Are you ready?

Aquí os dejamos cada texto del reading Aptis matching headings to paragraphs con sus respectivos párrafos, las opciones de headings o títulos (careful, que hay uno que sobra) y las respuestas al final de los textos. Si eres profesor preparador Aptis y utilizas nuestro material, menciona la fuente (tarde o temprano tus alumnos vas a encontrar este material en Internet ;). Estos ejercicios de readings Aptis están inspirados en artículos de la BBC, sin embargo el material Aptis con el que trabajamos en nuestras clases, también elaborado por nosotros, se intenta adaptar bastante a los temas reales de la prueba.

1. Victorian Sport: Playing by the Rules

A continuación os dejamos el primer ejercicio, mucha suerte!

A game of two halves - There are no rules - Laying down the law - Word gets around - Ashes to ashes - Fame and success

1. Heading:

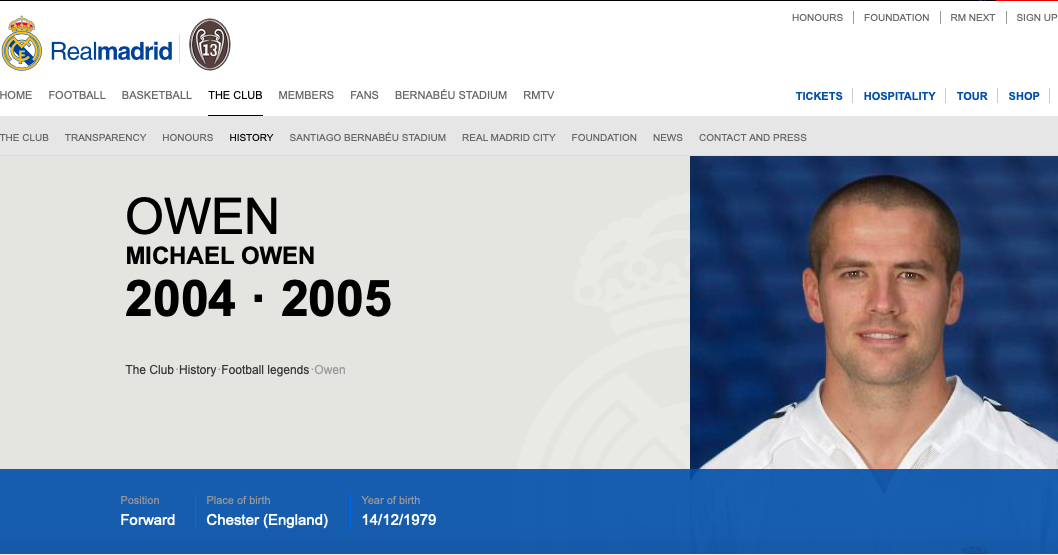

Michael Owen doubtless doesn’t know it, but he probably owes some of his success as a footballer to the Victorians. Before the 1800s, ‘football’ was a pretty rough pastime and a man of Michael’s size would have been at a distinct disadvantage. Had they existed, the laws of the game would have read something like this: rule one – there are no rules. Bone-crunching tackles were literally that, and there were no referees, blind, biased or otherwise, to offer protection.

In 1602, Sir Richard Carew described the Cornish hurling game, a forerunner of today’s field sports, thus: when the hurling is ended, you shall see them retyring home, as from a pitched battaile, with bloody pates, bones broken, and out of joynt, and such bruses as serve to shorten their daies.

Luckily for Michael, matters would change. The course of the Victorian period saw a drive towards a more civilised and controlled society. In sport this manifested itself by a desire for rules and regulations, changing the emphasis from manly physical pursuits to moral and spiritual exercises with disciplinary value and a spirit of fair play.

It was a process that was largely driven by the Industrial Revolution. Industry began to dominate the economy and workers moved from field to factory and developed a new-found desire for material wealth. This gave their middle class employers greater control and the chance to dictate how employees should live their lives. A campaign was mounted against violent sports like football which left men injured and unable to work, while working hours were increased to levels previously deemed unacceptable leaving fewer opportunities to play.

2. Heading:

But things were different in one area of society. In the public schools the aristocratic pupils held sway over their middle class teachers, and were free to play as they pleased. Nevertheless, parents were becoming concerned about the treatment of youngsters who, under the prefect-fagging system, were put in goal and suffered the brunt of the violence. Schools had to take action or face the prospect of parents taking their children elsewhere.

Thomas Arnold, headmaster at Rugby school, wanted his pupils to grow up into moral Christian gentlemen. He therefore moderated the prefect-fagging system and advocated regulated sports which provided exercise and encouraged healthy competition. By 1845, the pupils at Rugby felt it necessary for the first time to write down the rules of football at their school to establish exactly what constituted fair play. In the Rugby version, handling the ball was allowed, but, in 1849, pupils at Eton created a rival game. It may well have been an attempt to outdo the ‘upstarts’ at Rugby, but football Eton-style greatly restricted the use of the hands.

The pupils took their games with them to university, the only problem being that everyone played different versions. A need for a common set of rules arose and at Cambridge University four attempts were made in the 1840s and 1850s. Eventually, in 1863, they decided on a set of rules in which handling the ball was outlawed.

At the end of that year, players from around the country came together to form the Football Association and the Cambridge rules were adopted. It didn’t suit everybody, and the representative from the Blackheath club withdrew because he favoured the Rugby style of game. He also advocated a type of tackle that they called ‘hacking’ – these days we would probably call it GBH.

3. Heading:

So the modern games of football and rugby were born (although rugby would divide again into league and union games) and these sports were portrayed as healthy rather than destructive. Of course legend has it that rugby was invented in a moment of inspiration by one of the pupils at Rugby. A plaque on the school grounds reads:

This stone commemorates the exploit of William Webb Ellis who with a fine disregard for the rules of football, as played in his time, first took the ball in his arms and ran with it, thus originating the distinctive features of the rugby game. AD 1823

Sadly the evidence to support the myth is harder to find – still it’s a nice story.

The formation of the FA was a symptom of the desire for order prevalent at the time. Other sports soon followed suit – the Amateur Athletic Club was formed in 1866, the Rugby Football Union in 1871, and the Lawn Tennis Association in 1888. There was evidently a social aspect to these organisations (most were formed in pubs), but they enabled the establishment of rules and the arrangement of competitions. The first ever FA Cup followed in 1872. The Rev RWS Vidal, known as the ‘Prince of Dribblers’, lived up to his name and set up MP Betts to score the only goal as the Wanderers beat the Royal Engineers.

In tennis the cart came before the horse, with the first Wimbledon championships being held in 1877, 11 years before the launch of the LTA. The game’s birth can be traced back to 1858 when Major Henry Gem marked out the first court on a lawn in Edgbaston. But it was Major Walter Wingfield who developed the modern game of tennis. Helped by the invention of a rubber ball which would bounce on grass, he patented a game he catchily called ‘Sphairistike’ which used a ‘New and improved court for playing the ancient game of tennis’. Wingfield sold sets of his game for five guineas – they included balls, four racquets and netting to mark out the hourglass shaped court. Not surprisingly ‘Sphairistike’ did not stick, and the name lawn tennis was adopted.

At that stage croquet that was all the rage, but that was soon to change. We know it by a different name now, but in 1875 The All England Croquet Club at Wimbledon chose to adopt tennis, and a tournament for all-comers was organised two years later to raise funds. Twenty-two players paid £1.05 for the privilege of entering, and Spencer Gore went down in the history books as the first Wimbledon champion, although he later confessed that he thought tennis would never catch on. He was very quickly proved wrong.

4. Heading:

Many other great contests were born in the Victorian era. Cricket’s rules had been laid down as early as 1744, but in 1861 an English touring team travelled down under for the first time. Seven years later a team of Aborigines toured England, although the first official Test match was not until 1877 when Australia beat England in Melbourne. An inauspicious start, but worse was to come. When Australia won a Test in England for the first time in 1882, The Sporting Times published the famous obituary:

In affectionate remembrance of English cricket which died at the Oval on 29th August, 1882. Deeply lamented by a large circle of sorrowing friends and acquaintances. R.I.P. N.B. The body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia.

The ‘body’ is reputed to be one of the bails, and England and Australia have played for the Ashes ever since.

Like cricket, golf’s rules were first laid down in the 18th century, but it is the Victorians we have to thank for the Open Championship which was first played in 1861. Prior to that, there had been separate competitions for amateurs and pros as professionalism did not fit with sport’s new image. The Marylebone Cricket Club hired professionals for the menial tasks of bowling and fielding so the ‘gentlemen’ could practise their batting. This distinction between amateur batsmen and professional bowlers led to the annual matches between Gentlemen and Players.

But spectator interest in sport was growing, helped by improvements in transport, and entrepreneurs cottoned on to the fact that there was money to be made. Football was a particular money-spinner and clubs vied for the top players. While the ex-public schoolboys of the FA found the notion of the professional footballer ungentlemanly, they gave in to the threat of a block withdrawal from the FA Cup by a group of teams from the North and the Midlands. In 1885 professionalism was legalised and three years later a league was formed.

5. Heading:

Not happy with just laying down the rules in their own country, British settlers spread the gospel wherever they went. Even today, many Argentine and Brazilian football sides betray their roots with English names. Closer to home, Italian clubs such as AC Milan and Juventus, who got their famous playing strip from Notts County, also have English connections.

But it was not just football that the English migrants took with them. Rugby and cricket would flourish in Australia and New Zealand, while India and Pakistan took cricket to their hearts.

And so sport entered the 20th century with a new image. The Victorians had cleaned it up and repackaged it as a moral, exciting spiritual activity, rather than a rough pursuit dependent on physical prowess. Tennis and golf would go from strength to strength, while athletics would flourish, particularly with the establishment of the Olympic movement.

The factory owners, who once did all they could to prevent their workers playing sports like football, now changed their views as sport was more likely to keep their employees healthy. In fact many employers encouraged the formation of works teams to try to foster feelings of solidarity among the workforce. Dial Square, formed by workers at the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich in 1886, went on to become Arsenal FC; West Ham was formed by the workforce at Thames Iron Works in 1895; while Newton Heath, a club founded by workers from the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company, went on to become known by a slightly more familiar name – nowadays we call them Manchester United.

Answers Reading Aptis matching headings:

1º There are no rules; 2º A game of two halves; 3º Laying down the law; 4º Ashes to ashes; 5º Word gets around

2. The Cambridge Spies

Después del primero, viene el segundo. Poco a poco, ya estás cerca del final. Good luck!

Failure to trust - Looking for discrepancies - The early years - Dealing with suspicion - A world of shadows - Fake friends

1. Heading:

The hardest and most bitterly fought confrontation between the Soviet Union and the western democracies during the 50 years of the Cold War was on the espionage front. In this arena the KGB, the ‘sword and the shield’ of the USSR, pitted its wits against its principal adversaries – the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States (CIA) and the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS).

The aim of each was to steal the secrets of the other side, to try to peer inside the mind of the enemy, to fathom his intentions, and to neutralise them before they could be executed. The soldiers in this war were the spymasters, the spies and their agents, all of whom operated in an undercover world where deception and betrayal flourished.

During the spy war it was impossible to write authoritatively about it. The present author once wrote that the truth could not be told ‘until the files of the KGB, the CIA and the SIS are all opened to public scrutiny’ – little dreaming that this would ever happen.

But when Communism collapsed and the Cold War ended, this is exactly what did occur, and thus it became possible to tell the story of the four most remarkable spies of the Cold War, four larger-than-life Englishmen: HAR (Kim) Philby, Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean and Anthony Blunt, all of whom betrayed their country to spy for Moscow.

In the new political climate, it became possible to tell the story both from Britain’s point of view and through the eyes of the KGB. And from this tale we can draw some startling conclusions about the nature of espionage and its real value in the modern world.

2. Heading:

In the early 1930s, the democratic world appeared to be in trouble. The Great Depression had caused widespread unemployment. Fascism was on the march in Germany and Italy. To many young students at Cambridge University, privileged though they were, this was worrying and unacceptable.

Four of them – Philby, Burgess, Maclean and Blunt – wanted to do something about it. They believed that the democracies would prove too weak to stand up to Hitler and Mussolini, and they knew that many people in Britain did indeed admire these leaders. They also thought that only the Soviet Union would be powerful enough to defeat Fascism. So, when they were approached by a recruiter from Moscow, the four young men agreed to serve the KGB.

The KGB believed that recruiting clever people from a respected university was a good game plan, because the chances were that sometime in the future these young men would be among Britain’s rulers and well placed to betray their country’s secrets.

This is how it turned out. By the time World War Two was underway, Maclean was climbing the ladder in the Foreign Office, Burgess was an intimate of prominent politicians, and Blunt was an officer in the Security Service – MI5. Even more astoundingly, Philby was an officer in the SIS. And all the while they were establishing themselves in these positions, these four men were reporting to Moscow.

It got better for the KGB. Just before the war ended, Philby was appointed head of the SIS’s anti-Soviet section, so that the man who was charged with running operations against the Russians, was a Russian agent. Blunt, meanwhile, had been on the distribution list for material from the war’s most secret operation, Ultra, decoded German radio traffic.

Then, as the Cold War got under way, Philby became SIS liaison officer with the newly formed CIA in Washington, where Maclean was first secretary at the British embassy, sitting on a committee that dealt with atomic bomb matters.

Burgess at this time was with the Foreign Office news department. Put together, their information should have been of inestimable value to Moscow. But the KGB files on these dedicated Soviet agents show a different picture.

3. Heading:

Ever since the Bolshevik Revolution, when a British secret service plot nearly brought down the new Communist government, the KGB had regarded the SIS as the most sophisticated and ingenious of all the capitalist intelligence services, capable of all sorts of duplicity and convoluted conspiracies.

So although the KGB had recruited four young Englishmen who appeared dedicated to their cause, was it just possible that the SIS had deliberately placed these men in the path of the Russian recruiter? Was it possible that although the KGB believed that these four agents had penetrated the British establishment, the very opposite was the case – Philby, Burgess, Maclean and Blunt had instead penetrated the KGB?

The KGB files show that a powerful section of the KGB believed that this was the case. Officers argued that it had been all too easy for the Cambridge ring. Could the British authorities be so stupid to as to allow men of such left-wing backgrounds into positions of trust in the establishment? How could Philby, who had helped Communists escape from Vienna and had then married a Viennese Communist, get through the security checks that the SIS must carry out on all those it recruited?

This suspicion tainted the KGB careers of all four. None of them was entirely trusted. None of the important information they sent to Moscow was accepted at face value, unless it could be confirmed from other sources.

Moscow’s spymasters argued that they could not be sure they were not having disinformation deliberately fed to them, with the intention of misleading the KGB. And all the while the KGB wasted the agents’ valuable time by trying to trip them up, trying to prove that their loyalty really lay with Britain.

4. Heading:

With the Germans at the gates of Moscow in 1941, the KGB bombarded Philby with orders to write his autobiography yet again, hoping to find in the new version some discrepancy with which to tax him. Even the patient Philby, who is never known to have once said a bad word about the KGB, to anyone who spoke to him, got fed up.

His controller reported to Moscow: ‘We’ve recently raised the issue with ‘S’ about his submitting a summarising, complete and detailed autobiography, with notes on all his contacts, all his work with us, the English institutions, and the like. But ‘S’ says that he doesn’t have the time, that in his opinion, now is the time that attention should be paid primarily to getting information, and not to writing various biographies. We pointed out the error of his conclusions to ‘S’.’

And when Philby was not writing and re-writing reports about himself, the KGB wanted him to find out the names of Soviet citizens who might have been recruited by the SIS station chief in Moscow. When Philby looked at the SIS files, and reported that the SIS had not recruited anybody yet, the KGB asked Blunt the same question. When he confirmed Philby’s reply, the KGB concluded that this was evidence that Blunt was, like Philby, a British plant, and the British conspiracy to penetrate was more widespread that the KGB had imagined.

5. Heading:

Once the KGB had convinced itself that the Cambridge spy ring was most likely a British conspiracy against the Soviet Union it faced a difficult decision. How was it to handle this?

If it cut off all contact with the Cambridge ring and it later turned out that its agents were genuinely loyal to the USSR, then the KGB would be blamed. Those officers running the Cambridge ring might be accused of sabotage. They might be shot. All right, then, Moscow reasoned, let’s pretend that nothing has happened and do our best to reinforce Philby’s conviction that we trust him and his ring completely.

And so the game of deceit and double-dealing continued. The Cambridge spies were deceiving their colleagues, their service, their families and their country. They did this in the sincere belief that they were serving a greater cause, through an elite intelligence service, the KGB, which fathered and mothered them and appeared to trust them totally. But the KGB, in turn, was deceiving the Englishmen, because it really believed that they were playing a treble game and were all traitors to the Communist cause.

The conclusion from all this is that the main threat to intelligence agents comes not from the counter-intelligence service of the country in which they are operating, but from their own centre, their own people.

In a dirty bogus business, riddled with deceit, manipulation and betrayal, an intelligence service maintains it sanity by developing its own concept of what it believes to be the truth. Those agents who confirm this perceived truth – even if it is wrong – prosper. Those who deny it – even if they are right – fall under suspicion.

From that moment on, the better that agent’s information, the greater the suspicion with which he or she is treated. When other agents offer confirmation, the suspicion spreads, until the whole corrupt concern collapses, only for a new generation of paranoid personalities to start afresh. Knowing this, anyone interested in the spy world should reflect on the moral problems of espionage, and how they might be confronted.

Perhaps one way would to be to consider whether we need intelligence services in the 21st century. They are only a comparatively recent phenomenon (the SIS dates from 1911, the KGB from 1917, and the CIA from as recently as 1947). It could be that nations have been the victim of a vast confidence trick to deceive us about the necessity and the value of spies.

Answers Aptis reading matching headings:

1º A world of shadows, 2º The early years, 3º Failure to trust, 4º Looking for discrepancies, 5º Dealing with suspicion

Aquí tienes otro multiple choice reading Aptis para practicar.

3. Viking Religion

El siguiente va sobre vikingos. ¡Esperamos que te guste1

Co-existence - Conversion in Scandinavia - Gods and Giants - Religious issues - Pagan belief

The age of conversion

1 Heading:

The Viking Age was a period of considerable religious change in Scandinavia. Part of the popular image of the Vikings is that they were all pagans, with a hatred of the Christian Church, but this view is very misleading. The Vikings had many gods, and it was no problem for them to accept the Christian god alongside their own. Most scholars today believe that Viking attacks on Christian churches had nothing to do with religion, but more to do with the fact that monasteries were typically both wealthy and poorly defended, making them an easy target for plunder.

The Vikings came into contact with Christianity through their raids, and when they settled in lands with a Christian population, they adopted Christianity quite quickly. Although contemporary accounts say little about this, we can see it in the archaeological evidence. Pagans buried their dead with grave goods, but Christians normally didn’t, and this makes it relatively easy to spot the change in religion.

As well as conversion abroad, the Viking Age also saw a gradual conversion in Scandinavia itself, as Anglo-Saxon and German missionaries arrived to convert the pagans. By the mid-11th century, Christianity was well established in Denmark and most of Norway. It wasn’t until the mid-12th century that Christianity became established in Sweden. As part of the process of conversion the Christians took over traditional pagan sites.

2. Heading:

We know almost nothing about pagan religious practices in the Viking Age. There is little contemporary evidence, and although there are occasional references to paganism in the Viking sagas we have to remember that these were written down 200 years after the conversion to Christianity. We know that chieftains also had some sort of role as priests, and that pagan worship involved the sacrifice of horses, but not much more.

We know rather more about the stories associated with the pagan gods. Besides occasional references in early poems, these stories survived after conversion because it was possible to regard them simply as myths, rather than as the expression of religious beliefs. The main sources of evidence are the Eddas, wonderful literary works which represent the old pagan beliefs as folk tales. Even here there is some Christian influence. For example, the chief god Odin was sacrificed to himself by being hanged on a tree and pierced in the side with a spear, and this was followed by a sort of resurrection a few days later – a clear parallel with Christ’s crucifixion.

Even so, the Eddas provide a huge amount of information about the gods, and their relationship with giants, men and dwarfs. The most powerful god was the one-eyed Odin, the Allfather, god of warfare, justice, death, wisdom and poetry. Probably the most popular god, however, was Thor, who was stupid but incredibly strong. With his hammer Miollnir, crafted by the dwarfs, he was the main defender of the gods against the giants. He was also the god of thunder, and he was particularly worshipped by seafarers. Amulets of Thor’s hammer were popular throughout the Viking world. The brother and sister Frey and Freyja, the god and goddess of fertility, were also important, and there were many other minor gods and goddesses.

3. Heading:

The great enemies of the gods were the giants, and there were often conflicts between the two races. Among the gods, only Thor was a match for the giants in strength, so the gods usually had to rely on cunning to outwit the giants. Odin himself was capable of clever tricks, but whenever the gods needed a really cunning plan, they turned to the fire-god Loki. Like fire, which can bring necessary warmth or cause great destruction, Loki did many things that benefited the gods, but he also caused them great harm, and often the problems he solved had been caused by his mischief in the first place.

Despite the tension between gods and giants, there was a fair amount of contact on an individual basis, and a number of the gods had relationships with giantesses. One of these was Loki, who had three monstrous children by his giantess wife. His daughter Hel became ruler of the underworld. One son, Jormunagund, was a serpent who grew so large that he stretched all the way around the earth. The other son was Fenris, a wolf so powerful that he terrified the gods until they tricked him into allowing himself to be tied up with a magical chain which bound him until the end of time.

It was believed that the world would end with the final battle of Ragnarok, between the gods and the giants. Loki and his children would take the side of the giants. Thor and Jormunagund, who maintained a long-running feud with each other, would kill each other, and Odin would be killed by the Fenris wolf, who would then be killed in turn. A fire would sweep across the whole world, destroying both the gods and mankind. However, just enough members of both races would survive to start a new world.

4. Heading:

The raids on the Frankish kingdoms and the British Isles brought increased contact with Christianity. Although Vikings often seem to have maintained their beliefs throughout the periods of their raiding, there was considerable pressure to convert to Christianity if they wished to have more peaceful relations with the Christians.

Another more or less formal convention applied to trade, since Christians were not really supposed to trade with pagans. Although a full conversion does not seem to have been demanded of all Scandinavian traders, the custom of ‘primsigning’ (first-signing) was introduced. This was a halfway step, falling short of baptism, but indicating some willingness to accept Christianity, and this was often deemed to be enough to allow trading.

Further pressure came as Viking raiders settled down alongside Christian neighbours. Although scholars disagree on exactly how extensive the Scandinavian settlement was in different parts of the British Isles, few people would now accept that the Vikings completely replaced the native population in any area. In particular, the settlers often took native wives (or at least partners), although some settlers apparently brought their families over from Scandinavia. The children of these mixed marriages would therefore grow up in partially Christian households, and might even be brought up as Christians. Further intermarriage, coupled with the influence of the Church, gradually brought about a complete conversion.

5. Heading:

Attempts to convert Scandinavia began even before the Viking Age. The Anglo-Saxon St Willibrord led a mission to Denmark in 725, but although he was well-received by the king, his mission had little effect.

Archaeological evidence suggests that Christianity was adopted piecemeal in Norway, with settlements converting or not depending on whether the local chieftain converted. The same idea can also be seen on a larger scale. In the mid-tenth century Hakon the Good of Norway, who had been fostered in England, tried to use his royal authority to establish Christianity. However, when it became clear that this would lose him the support of pagan chieftains, he abandoned his attempts, and his Anglo-Saxon bishops were sent back to England.

Harald Bluetooth of Denmark was apparently more successful. His famous runestone at Jelling tells us that he ‘made the Danes Christian’, and this is supported both by Christian imagery on Danish coins from his reign and by German records of the establishment of bishops in various Danish towns.

Further attempts by Anglo-Saxon missionaries in the late tenth century had only a limited effect in Norway and Sweden. The latter, however, faced a pagan reaction in the mid-11th century, and it was not until the 12th century that Christianity became firmly established.

Answers Aptis reading matching headings:

1º The age of conversion, 2º Pagan belief, 3º Gods and giants, 4º Pagan and Christian together, 5º Conversion in Scandinavia

Fuente: BBC.CO.UK

4. Captain Cook: Explorer, Navigator and Pioneer

A continuación, vamos con el cuarto, este es muy interesante. Ánimo, tú puedes!

Putting the main outline of the coast of north west America on the maps - Prosecuting discoveries so much longer than any other man ever did - Antithesis of the crusader - Natural ability and dogged determination - Laying down the essentials of the modern map of the South Pacific - Mysterious journey

1º Heading:

The three major voyages of discovery of Captain James Cook provided his European masters with unprecedented information about the Pacific Ocean, and about those who lived on its islands and shores. His achievements were the more remarkable because of his humble origins in an agricultural labouring family, from Marton, North Yorkshire.

Cook first went to sea at the age of 18. He spent ten years working in the coal trade of the east coast of England – with its shoreline of treacherous, shifting shoals, uncharted shallows, and difficult harbours. In 1755 he joined the Royal Navy, and within two years passed his master’s examination to qualify for the navigation and handling of a royal ship. He gained surveying experience in North American waters during the Seven Years War – as Britain and France fought for supremacy in North America – and spent the first years of peace charting the fog-shrouded coastline of Newfoundland.

During those years he gained a practical training in mathematics and astronomy, and steadily accumulated the technical skills needed to make an effective explorer. The following years were to show that in addition he possessed those less tangible qualities, of leadership, determination and ambition, which made him the outstanding explorer of the 18th century. As he wrote, he intended to go not only ‘farther than any man has been before me, but as far as I think it possible for man to go’.

2. Heading:

Cook’s first voyage (1768-71) was a collaborative venture under the auspices of the Admiralty and the Royal Society. The original intention was to organise a scientific voyage to observe the transit of the planet Venus from Tahiti, and this was supplemented by instructions to search for the great southern continent, Terra Australis Incognita, whose location had intrigued and baffled European navigators and projectors since the 16th century.

With Lieutenant Cook sailed the botanist Joseph Banks, the astronomer Charles Green, and a small retinue of scientific assistants and artists. Cook’s ship, the Endeavour, was a bluff-bowed Whitby collier chosen for her strength, shallow draught, and storage capacity.

Cook sailed first to Tahiti to carry out those astronomical observations that were the initial reason for the voyage, before turning south where he sailed west to New Zealand, whose coasts he charted in a little over six months to show that they were not part of a southern continent.

From there Cook pointed the Endeavour towards the unexplored eastern parts of New Holland (the name given by the Dutch to Australia in the 17th century). Cook sailed north along the shores of present-day New South Wales and Queensland, charting as he went.

He then sailed through the Torres Strait, so settling the dispute as to whether New Holland and New Guinea were joined. With only one ship Cook had put more than 5,000 miles of previously unknown coastline on the map. The twin islands of New Zealand, the east coast of Australia and the Torres Strait had at last emerged from the mists of uncertainty

3. Heading:

Cook’s second voyage (1772-75) was the logical complement to what had been explored, and left unexplored, on his first. Again there were scientists and artists on board, and for the first time chronometers, one of which was Kendall’s copy of John Harrison’s famous no. 4 marine chronometer. This superb instrument kept accurate time throughout the buffeting it endured on the long voyage, showing that a practical solution to the problem of determining longitude at sea had been found.

In his three years away, the newly-promoted Captain Cook disposed of the imagined southern continent, reached closer to the South Pole than any previous navigator, and touched on many lands – Tahiti and New Zealand again, and for the first time Easter Island, the Marquesas Islands, Tonga and the New Hebrides.

Most of these places had been sighted by explorers on earlier expeditions, so that even by conventional definitions Cook did not ‘discover’ them for Europe. His contribution was to bring order to confusion, to replace vagueness and uncertainty with a scrupulous accuracy. He had, he explained, put an end to the search for the great southern continent.

4. Heading:

On his return from his second voyage, Cook found that his fame had spread beyond naval circles. Brief thoughts of retirement were replaced by a determination to return to the Pacific. Cook’s third and final voyage (1776-80) had its own logic in that it took him to the North Pacific in an effort to solve a geographical mystery as old as the southern continent – the question of the existence of a navigable north west passage.

As he approached the north west coast of America in 1778, Cook made the major discovery of the Hawaiian Islands, the northernmost outliers of Polynesia. He spent that summer in hazardous exploration along the American coast from Vancouver Island to the Bering Strait, searching in vain for the wide strait leading to an ice-free Arctic Ocean, as indicated on the speculative maps of the period.

Although he found no north west passage, in a single season Cook put the main outline of the coast of north west America on the maps, determined the shape of Alaska well beyond the Bering Strait, and closed the gap between the Spanish coastal probes from the south and those of the Russians from Kamchatka.

It was to be his last achievement, for the following winter he was killed on his return to the Hawaiian Islands. His death at Kealakekua Bay on 14 February 1779 has remained a source of scholarly controversy. During the weeks after his arrival Cook seems to have been regarded by the Hawaiians as the god Lono, bringer of light, peace and plenty, for he had arrived at the time of makahiki, Lono’s festival.

Cook continued to conform to the sacred calendar of the islanders by sailing away from Hawaii as makahiki came to an end. However, the Resolution got damaged at sea, so that Cook was forced to return to the bay to repair his ship out of the correct season, thus making himself a violator of sacred customs.

It was noted that there was an eerie atmosphere among the islanders following his return, and Cook’s death after an argument on the beach was predictable if not preordained. Not all accept this interpretation. Some scholars see Cook’s ‘deification’ as the product of a Western, imperialist tradition, and they explain his death as being the result of a row caused by one of his uncontrollable outbursts of temper, which had become increasingly noticeable during the voyage.

5. Heading:

The circumstances of Cook’s death were a reminder that one of his tasks was ‘to observe the Genius, Temper, Disposition and Number of the Natives’. This was easier said than done, for successive migrations across the Pacific had left societies organised in overlapping layers and groups, and the strained nature of the contact between Europeans and non-Europeans made understanding between them all the more difficult.

Cook and his fellow navigators of the period were for the most part humane and moderate commanders. Even so, the Europeans were intruders, emerging by the score from their towering vessels, appearing and disappearing without warning, violating sacred sites. An inescapable tension hung over the encounters, sometimes dissipated by individual contacts or trade, but often erupting into violence and death. Although the relationship between Polynesians and Europeans was not the one-sided affair of some portrayals, in the longer term the coming of venereal disease, alcohol and firearms brought a depressing train of consequences to the islands.

Cook set new standards in the extent and accuracy of his surveys, but to see his voyages simply in terms of geographical knowledge would be to miss their broader significance. The observations of Cook and his colleagues played an important role in natural history, astronomy, oceanography, philology and much else. Above all, the voyages helped to give birth in the next century to the new disciplines of ethnology and anthropology.

Answers Aptis reading matching headings:

1º Natural ability and dogged determination, 2º Prosecuting discoveries so much longer than any other man ever did, 3º Laying down the essentials of the modern map of the South Pacific, 4º Putting the main outline of the coast of north west America on the maps , 5º Antithesis of the crusader

Fuente: BBC.CO.UK

5. Florence Nightingale: Saving lives with statistics

Y para terminar, Florence Nightingale. Este es el último empujón y ya lo tienes. A por ello!

Florence takes the fight to India - The lady of the lamp hits the big time - Florence gets to work - Florence reveals the truth - The death toll rises - The Crimea calls - Healthcare for everyone - Florence passes away - The breakthrough - Florence hears God - A gifted child - A proposal

1. Heading:

Florence was named after the Italian city of her birth. She grew up on picturesque English country estates with her elder sister, Parthenope.

Her upper middle class upbringing included an extensive home education from Florence’s father, who taught his daughters classics, philosophy and modern languages. Florence excelled in mathematics and science. Her love of recording and organising information was clear from an early age – she documented her extensive shell collection with precisely drawn tables and lists.

2. Heading:

The Nightingales took their daughters on a tour of Europe, a custom intended to educate and refine gentlewomen in the 19th century.

But Florence’s unconventional character continued to develop, as entries from her diary of the trip show. She recorded detailed notes of population statistics, hospitals and other charitable institutions. In spite of her mother’s disapproval, she later received further tuition in mathematics. Yet her biggest rebellion was still to come. In 1837, she became convinced God had ‘called’ her to his service but her parents were horrified when she revealed what she thought the service should be…

3. Heading:

Florence was an eligible young woman – intelligent, striking and wealthy. Proposals were sure to come her way, but Florence had a proposal of her own.

Her family expected her to marry well but the prospect of a life of domesticity left Florence cold. By 1844, she had decided nursing was her calling. She proposed training in Salisbury, but her parents refused. They thought nursing was lowly, immodest work done by the poor or servants, completely unsuitable for a woman of Florence’s social standing. Florence, however, persevered. In 1849, after a long courtship, she even declined a proposal of marriage, believing her destiny lay outside wedlock.

4. Heading:

Nothing could sway Florence from her mission to nurse. She defied her parents’ wishes and continued to visit hospitals in Paris, Rome and London.

In 1850, realising his daughter was unlikely to marry, Florence’s father finally relented and allowed her to train as a nurse in Germany. Parthenope struggled to accept her sister’s hard-won independence and suffered a nervous breakdown in 1852. This forced Florence to return and care for her. But in August 1853, the breakthrough finally came: Florence became superintendent at a women’s hospital in Harley Street. After nearly a decade, she had realised her ambition of becoming a nurse.

5. Heading:

The Crimean War broke out in 1853. Newspaper reports from the front line told horror stories of the appalling conditions in British army hospitals.

Sidney Herbert, Secretary of State at War, knew Florence well. He appointed her to take 38 nurses to the military hospital in Scutari, Turkey. It was the first time women had been allowed to officially serve in the army. When she arrived, the Barrack Hospital was filthy – the floor was an inch thick with faeces. She set her nurses to work cleaning the hospital and ensured soldiers were properly fed and clothed. The regular troops were, for the first time, being treated with decency and respect.

6. Heading:

Florence’s best efforts to combat the rising death toll failed. It kept increasing relentlessly, with over four thousand deaths in a single winter.

Although she had made the hospital more efficient, it was no less deadly. In the spring of 1855, the British government sent out a Sanitary Commission to investigate the conditions at Scutari. It discovered the Barrack Hospital was built on a sewer, meaning patients were drinking contaminated water. The hospital, along with other British army hospitals, was flushed out and ventilation improved. Consequently, the death rate began to fall.

7. Heading:

When a portrait of Florence carrying a lamp and tending to patients appeared in the press, she quickly gained an army of die-hard Florence fans.

Her work in Scutari improving the living conditions of soldiers in hospitals was hailed by both the press and the public. Her family had to wade through a steady stream of poems posted to Florence – the Victorian equivalent of fan mail – and images of ‘the lady of the lamp’ were printed on bags, mats and souvenirs. But Florence was wary of her celebrity. Although she returned home a heroine, she kept a low profile by travelling under a pseudonym – Miss Smith.

8. Heading:

It wasn’t until after she had processed all she had learned at Scutari, that Florence used her fame as a powerful weapon in her mission to save lives.

Haunted by the appalling loss of life, Florence met with one of her biggest fans, Queen Victoria. With her backing, she persuaded the government to set up a Royal Commission into the health of the army. Leading statistician William Farr and John Sutherland of the Sanitary Commission helped her analyse vast amounts of complex army data. The truth she uncovered was shocking – 16,000 of the 18,000 deaths were not due to battle wounds but to preventable diseases, spread by poor sanitation.

9. Heading:

Florence knew her talent for statistics wouldn’t be enough to ensure her report hit home. It was time to prove her mastery of communication as well.

Rather than lists or tables, she represented the death toll in a revolutionary way. Her ‘rose diagram’ showed a sharp decrease in fatalities following the work of the Sanitary Commission – it fell by 99% in a single year. The diagram was so easy to understand it was widely republished and the public understood the army’s failings and the urgent need for change. In light of Florence’s work, new army medical, sanitary science and statistics departments were established to improve healthcare.

10. Heading:

Florence was ill but wealthy – she could afford to pay for private healthcare. But she knew most people in Victorian Britain couldn’t do the same.

Impoverished people could only care for one another. Florence’s Notes on Nursing aimed to educate people about ways to care for sick relatives and neighbours, but she still wanted to help the very poorest in society. She sent trained nurses into workhouses to help treat the needy. This attempt to make medical care readily available to everyone, regardless of their class or income, served as an early precursor to the National Health Service.

11. Heading:

Florence had been involved in improving the health of the British army in India since her experiences in Scutari.

By the 1880s, scientific knowledge had advanced to further support her reforming ideas. Like many medical practitioners, she now accepted germ theory, and so emphasised the need for uncontaminated water supplies for people in India. Still collecting data, she campaigned for famine relief and improved sanitary conditions to combat a high death toll that she believed was caused by conditions akin to those she’d witnessed in Scutari. Florence received reports from India until 1906.

12. Heading:

Before Florence died at the age of 90, she became the first woman to be awarded the Order of Merit.

The headstrong girl with a well-documented shell collection had achieved so much, in field once deemed unsuitable for women of her class. Often a lone female voice appealing to the Victorian establishment, her skill for communication and mathematics helped overhaul army and civilian healthcare and saved thousands from a gruesome death. She shrewdly used her public mandate to urge governments into action, enshrining sanitation and personal well-being in our healthcare culture.

Answers Reading Aptis matching headings:

1º A gifted child, 2º Florence hears God, 3º A proposal, 4º The breakthrough, 5º The Crimea calls, 6º The death toll rises, 7º The lady of the lamp hits the big time, 8º Florence gets to work, 9º Florence reveals the truth, 10º Healthcare for everyone, 11º Florence takes the fight to India, 12º Florence passes away

Fuente: BBB.CO.UK

Si quieres practicar muchos más readings Aptis matching headings, consulta nuestros cursos intensivos Aptis.